Quick search

CTRL+K

Quick search

CTRL+K

Dublin is the capital of the Republic of Ireland, where one of the major things on the bucket list is the Irish atmosphere, which is reflected in the famous Irish pubs with Irish music. It is part of Ireland that you must remember to bring home from the green island, and you will also find many nice sights, monuments and museums in and around the capital,

Dublin, however, is also much more than pubs and coziness in the centrally located Temple Bar district. This includes the Vikings’ historical settlement, the elegant and intellectual environment of Trinity College, the large shopping districts, the green, Georgian 18th-century parks in the middle of the city, and of course the famous statue of Molly Malone.

There are also several interesting church buildings in Dublin. Several of them date back to the 12th century, and the city’s cathedrals have a unique status as formal cathedrals for both Protestants and Catholics. St. Patrick’s Cathedral and Christ Church Cathedral are the major religious attractions in the city.

Ireland is called the Green Island, and if you take a look in the countryside around Dublin you instantly see why. The nature is lovely and there is a relaxed country life, which unfolds close to the metropolis. If you want to see some wild nature, the hilly terrain around the Wicklow Mountains and the Irish East Coast are good opportunities for beautiful hikes and panoramas.

Trinity College is Dublin’s traditional university, founded under Queen Elizabeth I in 1592. It was established with the universities of Oxford and Cambridge as models, and the site is Ireland’s most famous educational institution today.

Trinity College is one of seven ancient universities in the British Isles and is Ireland’s most prestigious educational institution. Academically, the place belongs to the European top, and the university has a years-long and broad-based collaboration with the universities in the English cities of Oxford and Cambridge.

The Pope founded the first university in Dublin in 1311, and it functioned until the Anglican Reformation in 1539. Throughout much of the 16th century, there was debate about establishing a new university to replace the closed one, and the result was the establishment of Trinity College in 1592.

Building-wise, Trinity College developed throughout the 18th century towards the university you can experience today. Parliament allocated the university considerable resources for new buildings, and the first building of the time was erected from 1712. It was a library building, which today is called the Old Library. After the library, the Printing House and Dining Hall were built. In the latter half of the 18th century, the building complexes around Parliament Square were completed, while the buildings around Botany Bay were the last to be built; it was in the early 19th century.

During the first centuries, Trinity College was largely reserved for Anglicans, but from the middle of the 19th century Catholics could also apply for scholarships and other things relevant to study and research life at the university. Women gained full access to the institution in 1904.

Trinity College is located in the heart of Dublin, and in the inner courtyards there is a lovely calmness, and architecturally the buildings face the courtyards, so it is from here that you can best experience the university. There are several entrances to Trinity College with the main entrance from College Green. It is the western part of Trinity College that is worth seeing, and the central facilities are around Parliament Square and Library Square.

The entrance from College Green is through the Regent House building, and then you can see the university’s iconic landmark, the Bell Tower/ Campanile. The 30 meter high tower was donated by Lord John Beresford, who was the Archbishop of Armagh, and it was completed in 1853. Before reaching the Campanile, a colonnaded building is located on each side of the square. To the north you can see the university’s chapel, and to the south is the local theater building.

To the east of the Campanile is Library Square, whose northern side is built up with the neo-Victorian Graduates Memorial Building from 1897. To the east is The Rubrics building, which is the oldest building in the area; it was built around the year 1700.

On the south side of Library Square is Det Gamle Bibliotek/Old Library, which is undoubtedly the best-known place at Trinity College. The architectural highlight is the impressive Long Room, which is 64 meters long and houses 200,000 antique printed works. In the Long Room you will also find the country’s oldest harp, which is both an instrument and the country’s national symbol.

The Old Library houses some of Ireland’s greatest treasures. This primarily applies to the Book of Kells, which is located in a separate room. The Book of Kells is a copy of the Gospels in Latin, which is believed to have been made by monks in approximately the year 800. The book is considered to be the masterpiece among Celtic manuscripts.

In the area around the Old Library you can also experience other collections about museums. These are the Zoological Museum/Zoological Museum, the Science Gallery/Science Gallery and the Douglas Hyde Gallery/Douglas Hyde Galley, which continuously exhibits various contemporary art. You can also see the fine building, Museum House, which was built in the 1850s for the university’s geological collections.

This museum first opened its doors in 1890, and as the country’s national museum it naturally has fine collections, where you get a solid and well-presented impression of Ireland’s art, culture and natural history. However, you can also experience effects from other world cultures.

Finds from the past several millennia from various locations in Ireland form the core of the museum’s archaeological collection, which is housed in the building on Kildare Street. The departments with Celtic art, effects from the Viking Age and the so-called Irish Gold are among the most interesting, and parts of them are among Europe’s finest antique collections.

The building on Kildare Street is the National Museum’s main building and was built in 1890 to the designs of Thomas Newenham Deane to house the Dublin Museum of Science and Art.

Today, the National Museum also has branches elsewhere in Dublin and Ireland than on Kildare Street. On Merrion Street you can see the Department of Natural History, the art collection can be seen at Collins Barracks (Benburb Street) and you can see an exhibition about country life around Turlough Village was Castlebar.

Christ Church Cathedral is the cathedral of the Anglican Church of Ireland, and it has been the seat of the church’s archbishop since the English Reformation. At the same time, the cathedral is also nominally the seat of the area’s Catholic archbishop, although he uses St. Mary’s as a functioning cathedral.

The history of the church dates back to the years after King Sitric Silkenbeard’s pilgrimage to Rome in 1028. It is believed that the Vikings built a wooden church on this site in the 1030s, and it was the precursor to the current church building.

The Vikings’ church was located at their settlement around the present Wood Quay. It was one of two churches within the city walls; there was also an older Celtic-Christian church here. The wooden church from the 1030s, however, only survived until the 12th century, when the Earls of Pembroke, nicknamed Strongbow, had come to power.

The earls had the first church demolished and replaced it with a stone church, and thus the current Christ Church Cathedral was founded. The church building was completed in 1240, but it was rebuilt and extended right into the 19th century, with a major restoration taking place in the 1870s of the Victorian era. During the restoration, some new furnishings were added, and the difference between the medieval church and the rebuilt one was partly blurred.

Christ Church Cathedral has been the cathedral of Dublin’s Protestant congregation since the Reformation. It was King Henry VIII who granted the church that status in 1539.

The Gothic church room is 25 meters high, and here the second Strongbow is buried. It is interesting to see the interior of the church and the remains from both the original Viking church and parts of the earlier stone constructions from the 12th and 13th centuries. The 63 meter long crypt is an example of the facility from the 1170s.

In Dublin, there are two large, old Anglican churches, both of which have the title of cathedral, and in addition there is an executive Catholic pro-cathedral that ecclesiastically regards one of the Anglican churches as their cathedral. St. Patrick’s Cathedral is one of the Anglican cathedrals, and it is considered the national cathedral of the Anglican Church of Ireland.

St. Patrick’s Cathedral was founded in 1191, and it is today Ireland’s largest church building. The church’s current appearance and size derives mainly from extensions in the years 1191-1270. The style is early English Gothic, and it is a beautiful church space that you can experience here. The mosaic floor and the vaulted Gothic rooms and chapels are the parts of the building that make the biggest impression.

Today, St. Patrick’s Cathedral used for major recurring events such as the commemoration of the armistice agreement in 1918 on 11 November on the so-called Remembrance Day. Over time, the church has also laid floors for ceremonies such as two funerals of Irish presidents.

The Temple Bar neighborhood, which consists of relatively low houses around a series of narrow streets, was a run-down slum until the 1960s. Now one of Dublin’s most popular due to its cozy streets and very enjoyable nightlife and nightlife,

In the early 1990s, the area underwent a fine and thorough restoration, which led to a colossal transformation to what you can experience today. Culture is flourishing and a stroll around the narrow streets offers entertainment as well as many galleries and small shops.

As a neighbourhood, Temple Bar lies south of the River Liffey and is bounded by the Liffey to the north, Dame Street to the south, Westmoreland Street to the east and Fishamble Street to the west. In the Middle Ages, the area was a suburb outside Dublin’s city walls, and in the 14th century it was abandoned due to attacks from the Irish population. The neighborhood was newly laid out in the 17th century, and it was done initially as gardens for wealthy English families.

One of the families was headed by Sir William Temple, and he built a house here. The neighborhood is believed to be either named after William Temple or the Temple Bar District in London, and it was quickly developed as part of the Liffey’s former swamp area was filled up.

Dublin Castle is a large building that throughout history has had a significant political impact on Dublin and Ireland. From here, Ireland has been ruled over the centuries, and today Dublin Castle is the government complex of the Republic of Ireland.

The history of Dublin Castle began in 1204, when the English King John founded the construction of a defense against the Normans, who had invaded Ireland in 1169. The castle was completed around 1230 with defensive walls and moats, which should be able to withstand attacks against the city. The river Poddle was used as a natural defense on two sides of the castle, and wooden buildings were built behind the walls.

During the Middle Ages, the central wooden building was replaced by a larger stone house, which was used as both a government building, court and for various banquets and representative purposes. The house was called the Great Hall and stood until 1673, when it was destroyed by fire. Today, there is only the round fortress tower Record Tower, which stands from the original castle. The Record Tower dates from the late 1220s.

The current facility is more of a castle than a castle, and it mainly dates from the 18th century. The most important rooms and halls are located in the so-called State Apartments, which were residences and representation rooms for the Lord Lieutenant, who historically was the highest authority of the English and British monarch in Ireland.

Today, the State Apartments are used by the Irish government for major events such as state visits. It is also where the Irish presidents are officially installed in office every seven years.

Saint Patrick’s Hall is the largest hall in the State Apartments. The hall is beautifully furnished and was a ballroom when the British Lord Lieutenant lived here. Saint Patrick’s Hall was established in the 1740s and changed in decoration to the present in the 1790s. The ceiling is painted by Vincenzo Valdre, and its three panels depict the coronation of King George III, Saint Patrick’s introduction of Christianity to Ireland, and the recognition of King Henry II by the Irish chieftains.

The Throne Room is another important room. It was furnished around 1790, and the throne originates from King George IV’s visit to Ireland in 1821. The State Drawing Room was once built as the primary reception room for the British Lord Lieutenant, and the State Dining Room from the 1740s was the private dining room for the monarch’s representative. State Corridor is another fine space; the corridor dates from the 1750s and stands as one of the most elegant architectural elements in Dublin Castle.

Built from 1729 to house the Irish Parliament, this building is therefore of particular historical interest. The name of the building is also known as Parliament/Parliament House, and it served as the seat of both the House of Commons and the House of Lords in the Kingdom of Ireland until the year 1800. With the so-called Act of Union from 1800, the Kingdom of Ireland was dissolved and Ireland instead became part of the union United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland.

The Irish Parliament was located in Chichester House from the 17th century. By the beginning of the 18th century, this building had become dilapidated and too small to house the parliament. In 1727 it was therefore decided to spend £6,000 on a new building which became the present Parliament House. The building was designed by the architect Edward Pearce and built in the years 1729-1739.

Pearce’s original building is only part of the present complex on the site, and his work can be seen to the south with columns and colonnades. In 1787-1787 Parliament was extended with the portico to the east, and it was James Gandon who was behind the extension, which formed the entrance to the Irish upper house, the House of Lords. In 1787 the extension of Parliament to the west and the street Foster Place were also built. It happened by Robert Parke’s design.

When Parliament moved to London with the Act of Union in 1800, the Irish national bank, Bank of Ireland, took over the place. It happened with a clause that the former parliament building could no longer be used for political purposes. The Bank of Ireland was based here until the 1970s, when the institution moved to a modern building in Lower Baggot Street; in 2010 the bank moved to an address on Mespil Road.

Today, it is the House of Lords’ former meeting room that has been preserved as the most remarkable room in the building complex. Here you can experience an impressive hall with large 18th-century wall paintings and a fine chandelier from 1765. The House of Commons was the House of Commons, and their meeting hall was furnished with the Bank of Ireland as the central banking hall.

Irish folk music and Irish songs are known over large parts of the world, and popular songs include the song about Molly Malone. In the show, the girl Molly Malone walks the streets of Dublin selling seafood from her cart. Molly Malone is so far a fictional character, but many people have had a similar name over the years, and the much-sung Molly Malone’s life could well have taken place in historic Dublin. Some point to the fact that the story in the show could have been taken from the life of the real Irish capital in the 17th century.

Today, a statue of Molly Malone can be seen next to St. Andrew’s Church. Designed by Jeanne Rynhart, the statue was unveiled on 13 June 1988 during Dublin’s centenary celebrations. The statue originally stood on Grafton Street and it is planned to move it back there. By the way, June 13th bears the title of Molly Malone Day, and it is celebrated every year.

Custom House is the name of Dublin’s distinguished old customs building, which was built in neoclassical style in the years 1781-1791. It was the architect James Gandon who designed the large building, the facades of which were adorned with coats of arms and sculptures symbolizing Ireland’s rivers.

The customs functions in the Custom House were after some time transferred to London, and instead various public offices such as the tax police were set up in the large building, and thus it never came to be empty. Dublin’s port had also moved away from the city centre, and the Custom House’s location was therefore no longer as central as in the 1790s.

In 1921, the Custom House was badly damaged in a fire, and a rebuild was carried out over the following five years. However, the work only partially completed the town’s customs house, and it took until 1991 before the building was fully restored.

Today, exhibitions about the history of the Custom House are set up here, and you can also take a closer look at James Gandon’s buildings in Ireland. Gandon was born in English London in 1743, and the Custom House was his largest large-scale project.

Dublin is known for its Georgian neighborhoods. The rows of houses around Merrion Square are a magnificent example of precisely this type of architectural structure. The period is the 18th century, when there was economic prosperity and thus great building activity in Ireland.

It is recommended to take a walk around the square to really experience the houses and thus the typical impression of the period. The north side in particular is characteristically Georgian with the decoration of the houses’ entrances, wrought iron balconies, the colors of the doors and other characteristics that make the houses of this period so attractive in the streetscape.

The square was laid out in 1762 and was largely expanded in the early 1800s. It was not least the Earl of Kildare’s construction of a new residence, Leinster House, that made this area south of the River Liffey popular. With the construction of Leinster House, Merrion Square, Fitzwilliam Square and St. Stephen’s Green all laid out, and many of the city’s leading figures moved from the north side of the city to new townhouses around the squares.

At Merrion Square, in the square’s small park, you can see a statue of Oscar Wilde, who lived at the address Merrion Square 1 in the years 1855-1876. Originally, the Wellington Testimonial memorial was to have been erected in the square to commemorate Arthur Wellesley’s military victories, but due to resident protests it was instead erected in Phoenix Park. There is public access to the park at Merrion Square, but until the 1960s access was only available to residents with their own key.

O’Connell Street is Dublin’s main thoroughfare. The street is about 500 meters long and it is up to 49 meters wide. The street was called Drogheda Street back in the 17th century, and it was not until the 18th century that the current O’Connell Street was created as a street.

It was Henry Moore who, as Earl of Drogheda, had laid out the 17th-century street, and in the following century the banker and property man Luke Gardiner expanded the street according to the European model. Curtains would create a tree-lined boulevard of beautiful mansions and townhouses.

Luke Gardiner’s original site did not extend to the River Liffey, but an extension was the idea with the new street. Gardiner died in 1755 before this extension to the Liffey had been completed. The city government in Dublin chose to implement the plans later in the 18th century, and thus one of the most elegant streets in Europe of the time arose. Gardiner called the new street Sackville Street, and it was named after the then Lord Lieutenant, Lionel Cranfield Sackville.

The street retained the name Sackville Street until 1924, when it was named after Daniel O’Connell in memory of his political struggle in the 19th century for Catholic and Irish freedom in Great Britain.

Today there are not many original houses left, but after a series of demolitions in the 1970s in particular, new ones have been built, and there is also a lot of art and statues to see.

The most impressive building is the General Post Office, and of the monuments, the O’Connell Monument and the Spire of Dublin are probably the most well-known and worth seeing. The Spire of Dublin is a 120 meter high spire made of stainless steel, which was designed by Ian Ritchie Architects and completed in 2003.

On the site of the Spire of Dublin, Nelson’s Pillar stood in the years 1808-1966, when the monument was destroyed by a bomb blast.

Grafton Street is the name of Dublin’s most popular shopping street. The street stretches from St Stephen’s Green to the south to College Green to the north, and it is therefore centrally located in the Irish capital.

Grafton Street is named after Henry FitzRoy, who held the title of 1st Duke of Grafton. FitzRoy was the unofficial son of Charles II of England, who owned land on the site of present-day Grafton Street. The street was developed and thus effectively laid out by the Dawson family from the year 1708, and Grafton Street became a popular residential area. With the later construction of Carlisle Bridge, the current O’Connell Bridge, Grafton Street changed to be one of the city’s busy streets.

The Four Courts is the name of this building, which houses four of the Republic of Ireland’s most important courts; The Supreme Court, the Court of Appeal, the highest civil and criminal court called the High Court and the local court Dublin Circuit Court.

However, the name Four Courts comes from the British era, when the building was built for the Court of Chancery, Court of King’s Bench, Court of Exchequer and Court of Common Pleas respectively.

The large courthouse was built in the period 1776-1802. The first part of the design was drawn by Thomas Cooley and completed by James Gandon after Cooley’s death in 1784. Gandon was also behind, among other things, the Custom House in Dublin and has thereby left a distinguished architectural mark on the city.

Historically, the Four Courts’ quiet existence as administrative court offices was significantly changed in the first half of the 20th century. 1922 was the year a group of Irish people occupied the building in protest against the Anglo-Irish Treaty that had established Ireland as part of the British Empire. The Four Courts were bombed and destroyed during this occupation.

In the following years, the Four Courts was rebuilt according to original designs, and the site was reopened in 1932. In the building under the large dome, you can see and read about its history.

The world-famous author James Joyce was born in Dublin, where all his great stories take place. Ulysses is his most famous book and it is based on real life in Dublin on June 16, 1904.

The James Joyce Center is housed in the Earl of Kenmare’s town house from 1784, and here you can see a fine Georgian interior. The exhibition itself in the center examines James Joyce’s life and of course his works. If you are interested, you can get information on the spot about walks in the area where James Joyce or the characters in Ulysses have had their time.

On the western outskirts of Dublin lies the 712-hectare green area called Phoenix Park. It is a very popular park, which is used extensively by locals, and there are also many activities and a lot to see for visitors to the city.

The Phoenix Park area was conquered by the Normans in the 12th century, and the land here was given to the Order of St. John, which from the 16th century was known as the Order of Malta. The Knights of the Order established an abbey here, but they lost the land when King Henry VIII dissolved the monasteries in 1537. In the 17th century, the land passed to the king’s representatives in Ireland, and in 1662 the later park was laid out as a hunting ground. The park got its current size in 1680 and it was opened to the public in 1745.

You can take lovely walks in Phoenix Park along paths and over large lawns. There are wild game in the park, and you can also visit Dublin Zoo here. The garden opened in 1831 with animals from the English London Society.

You can also see several of Dublin’s most important monuments around Phoenix Park. The Wellington Testimonial is seen at the entrance to the park. It is a 62 meter high obelisk that was erected to commemorate the Duke of Wellington’s victories during the Napoleonic Wars. The obelisk is the tallest in Europe, and it should have been even higher, but during construction the project ran out of money. The Wellington Testimonial was originally intended for a square in Merrion Square, but the square’s residents protested, so the installation was moved.

Another monument is the Phoenix Column, which consists of a central column with a bird Phoenix rising from the ashes. It was Lord Chesterfield who had the Phoenix Monument erected in 1747. You can also see the Papal Cross in Phoenix Park. It has been erected on the very spot where Pope John Paul II held mass in 1979 for more than a million Irish people.

Between the monuments and the lawns is the official residence of the Irish president, Residence of the President/Áras an Uachtaráin. The house was completed in 1751 according to Nathaniel Clements’ design. In the 1780s, Clements’ house was acquired by the British monarch’s representative in Ireland and used as a somme’s residence, thereby supplementing the viceroy’s quarters at Dublin Castle. Since then, the building was named Viceregal Lodge, and the viceroys lived here for most of the year. They mainly used Dublin Castle from January to March, when there were many social duties.

In his time, it was not only the viceroy who had an official residence here in Phoenix Park. The same applied to the appointed Chief Secretary and Under Secretary who worked during the British era. The residence of the Chief Secretary is today the American ambassador’s residence, but the Under Secretary’s residence has been demolished.

In the 1900s, the American Chester Beatty donated his unique collection of literature and manuscripts to the city of Dublin. Among other things, you can see up to 6,000-year-old stone tablets, papyrus, beautiful editions of the Bible and many Asian books that have been prepared in unusual materials such as bark or jade. The library was founded in 1950 and since the year 2000 it has been located in its current location at Dublin Castle.

If you want to go out into Ireland’s wild nature, the large hilly area, the Wicklow Mountains, is a particularly good choice. It is Ireland’s largest total highland and it gives a fine impression of some of the country’s various scenic glories.

Designated as a national park, the Wicklow Mountains feature windswept, desolate pastures juxtaposed with rolling hills, rugged mountains and picturesque lakes. All in all, it is a beautiful and very characteristic landscape to be in.

It is a good idea to go around and enjoy the different viewpoints that are in the Wicklow Mountains. If necessary, follow the Military Road, a route of almost 100 kilometres, which was built in the year 1800 to make the area more passable. You can also see the region’s highest mountain, Lugnaquilla, whose peak reaches 925 meters. From the top you can see the south west mountains of Ireland and also to Wales on a clear day.

Glendalough is a small town that is incredibly beautiful in an elongated valley by two lakes in the Wicklow Mountains. In Glendalough, there are monastic ruins dating all the way back to the saint St. Kevin’s first buildings from the 5th century. Kevin founded Glendalough and was the first abbot of the place.

Over time, the monastery was often attacked by Vikings, but nevertheless it flourished for many centuries, until soldiers had attacked the area in 1398. Here began the decline of the monastery, which finally became the dissolution of the Irish monasteries in 1539, which King Henry VIII carried out.

Over time, many buildings other than Sankt Kevin’s original buildings have been built. The majority of the ruins that remain today are believed to be from the 7th-11th centuries, and among them stands the characteristic 30-metre round tower, which is Ireland’s best-preserved of its kind.

The round tower is located in the churchyard, where you can also see the ruins of Glendalough’s cathedral from the 12th century. Here you should note Saint Kevin’s Cross/St. Kevin’s Cross, which dates from the same time. The cross is one of the typical circular crosses, which is an early cross that combines the Christian cross with the sun and moon worship of the pagans of that time. The ring of the cross symbolizes the sun and should ensure a habituation to the Christian symbols and Christianity.

On a trip to Glendalough you can go to Upper Lake. Here are some older building remains that are believed to have been the place where Saint Kevin himself lived. It is believed that St. Kevin’s Cell was his home.

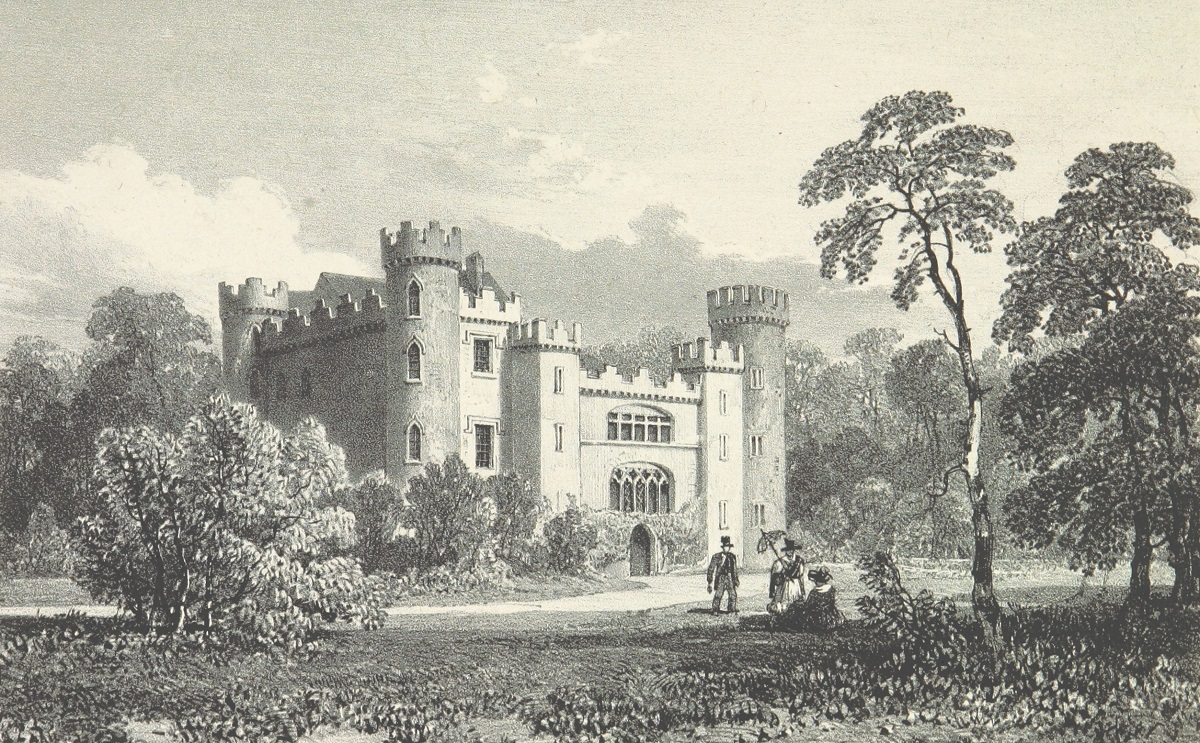

Malahide Castle is located in the town of Malahide, and it looks like a real knight’s castle with the facility’s characteristic towers. The history of the castle started with the knight Richard Talbot, who came to Ireland with King Henry II in 1174. Talbot was given the land and harbor at Malahide, and the oldest parts of Talbot’s residence date from the 12th century.

Over the centuries, the castle was owned by the Talbot family, they lived here for 791 years from 1185 to 1976. The only exception in that long period was in the years 1649-1660, when Oliver Cromwell had come to power in London. He presented Malahide Castle to Miles Corbet, who after the fall of Cromwell had to leave the place, which reverted to the ownership of the Talbot family.

Today, Malahide Castle is owned by the local authority, and a cafe and shop have been set up on site. You can also experience the castle itself, where a typical Irish 18th-century interior prevails in the rooms and halls, the most famous of which are the Oak Room and the Great Hall. Among other things, there are many portrait paintings in the castle where you can see the history of the Talbot family.

Behind Malahide Castle is Talbot Botanic Gardens, which offers large lawns, fine planting, several greenhouses and a Victorian conservatory. The garden is a beautiful example of a landscaped, 18th-century garden, where belts of trees and plants surround the lawns. There are many growths from southern climes such as Australia, and you can also see the 7th Lord Talbot’s collections from the middle of the 20th century.

Newgrange is a structure located in the open countryside west of the town of Drogheda. The facility was established as a burial mound and consists of a large central mound of earth surrounded by two rows of stone blocks. Construction is dated to around 3200 BC. Newgrange was added to UNESCO’s World Heritage List in 1993.

Newgrange lay hidden as part of the landscape for over 4,000 years before the site was rediscovered at the end of the 16th century. They chose to carry out a thorough restoration in the period 1962-1975, and since then you have been able to experience what is regarded as Ireland’s most important Neolithic monument.

The fine entrance gate to the facility was created during the restoration work based on an assessment of how Newgrange looked in its time. However, it is not known for certain what the place looked like.

Castletown House is a large country house that was built in the Palladian style in the years 1722-1732 for the Irish Speaker of Parliament, William Conolly. The Palladian style is Italian, and the architect of the mansion was the Florentine Alessandro Galilei.

The building itself is an impressive structure, where you can see a particularly fine 18th century interior. On the house’s piano nobile, there are a number of beautiful presentation rooms and halls. Among them is the State Bedroom, where the Viceroys of Ireland stayed several times during their visits to Castletown House. All in all, the house’s beautiful rooms give a good insight into the lifestyle of the Irish wealthy of the time.

At Castletown House there is also a fine art collection, and you can also enjoy a walk in the park around the mansion. The park is a recreated garden from the 18th century.

Drogheda is a town located in the north-east of Ireland on the banks of the River Boyne. The town has an interesting history dating back to two separate towns named Drogheda-in-Meath and Drogheda-in-Oriel. This was because the River Boyne formed a boundary between two Norman kingdoms, and the towns were merged into Drogheda in 1412. The old boundary continues today as the diocesan boundary between Meath in the south and Armagh in the north.

Over the centuries Drogheda became an important town under English rule and city walls were built around it. Over the past centuries, Drogheda has been developed as an industrial town, and in the 1800s, railways came to Drogheda, and shipping to England prospered.

Dundalk is a town located along the Castletown River on the east coast of Ireland. The area has been inhabited since Neolithic times, while the town of Dundalk was established as a Norman fortress after 1169. In the 14th century, the town was attacked, destroyed and taken by Edward the Bruce, and attacks continued for the following centuries, due to Dundalk’s status as a fortified border town towards Ulster in the north.

Throughout the 17th century, the city changed hands several times between the English and Irish Catholics. In the 18th century, Dundalk had become English, and the town could develop peacefully. Dundalk’s current town plan was largely laid out during this time. In the 1800s, the town developed industrially, but the 1900s again made Dundalk a border town, this time at the border with Northern Ireland.

Blanchardstown

blanchardstowncentre.com

Sandyford Road/Dundrum Bypass

dundrum.ie

Henry Street

jervis.ie

Coldcut Road/N4

liffeyvalley.ie

59 South William Street

powerscourtcentre.com

St. Stephen’s Green

stephensgreen.com

Grafton Street, O’Connell Street, Henry Street, Temple Bar District

Dracula Experience

Clontarf Road

draculaexperience.com

Dublin Zoo

Phoenix Park

dublinzoo.ie

Wax Museum

Granby Row, Parnell Square

National Aquatic Centre

Snugborough Road

nationalaquaticcentre.ie

Viking Splash Tours

St. Stephen’s Green

vikingsplash.com/

Danish Vikings founded Dublin in the area around today’s Wood Quai, and many objects from this early era in the city’s history have since been found. The Vikings named their new city after the local Dubh Linn, which was the term for a wetland at the confluence of the Liffey and Poddle rivers.

Dublin’s official founding took place in 988, though remnants of former occupations go further back. The Viking settlement was founded in 841, but the year 988 was chosen, marking the year when the Viking king Glun larainn accepted Máel Sechnaill II as the high king of Ireland.

Among other things, the Vikings’ time offered legislative meetings, which they also know from Iceland. They took place on the Thingmote hill, which was south of Liffey at the present Dublin Castle. The Vikings had the city and the area under control until the Irish launched several attacks; in 1052, 1075 and 1124. The era of the Vikings in Dublin ended in 1171 with the defeat of King Henry II of England.

Englishmen and Welsh settled in great style in and around Dublin from 1171 and maintained control of the Irish East Coast for several centuries. Dublin’s old town was on the south side of Liffey, and during those years a settlement also arose on the north side. It was the so-called Ostmantown. Dublin was at this time the capital of the English Lordship of Ireland.

Several major buildings were started in the former English Dublin. This included the churches of St. St. Patrick’s Cathedral, Christ Church Cathedral and St. Audoen’s Church. The churches were close to each other in what was the center of the capital of the time.

However, Dublin did not only develop in peace and quiet. The city was surrounded by city walls, and over the years Irish from the island’s vast and relatively desolate lands attacked numerous times. The 1300s also became a century of turmoil. Partly there was an unsuccessful attempt at invasion by Scotland under Edward the Bruce, and partly the plague hit the city in 1348. The disease, moreover, came not only to Dublin in the mid-1300s, but several times to 1649.

Dublin paid ongoing taxes to surrounding Irish communities to keep the clans from attacking the city. At the same time, the English interest in Ireland diminished, so Dublin was increasingly left to its own rule under some form of reliance on a good relationship with the Irish.

The British crown allowed the earls of Kildare to administer Ireland, and they increasingly did so based on their own interests. It ended with Garret Fitzgerald, Earl of Kildare, imprisoned. That event led to an Irish siege of Dublin Castle, prompting King Henry VIII to send English troops to Dublin.

The king’s military overcame the earls’ strengths and rule, and Henry VIII deployed English administrators, who then led the development of Dublin and Ireland. The King introduced new structures, and among other things he demolished the Irish monasteries in the late 1530s.

Catholic Europe was increasingly through the 16th century with the Protestant Reformation, which also came to England and made the country Anglican. The same was true of the English king and it was in contrast to the Irish people.

After closing the Irish monasteries that were Catholic, it came through the remainder of the 16th century for several settlements between the Protestant regime and the Catholic Irish. Dublin’s then mayor died in captivity at Dublin Castle in 1584 after being jailed for sympathy for Catholics, and Catholic Archbishop Dermot O’Hurley was hanged outside Dublin’s walls that year.

Queen Elizabeth I had arrived on the British throne in the early 1590s, and in 1592 she founded the University of Trinity College, modeled on the universities of Oxford and Cambridge. Trinity College was Anglican, and despite its high standard, wealthy Irish Catholics largely chose to send their children to Catholic universities around Europe instead of Trinity College. The reign of Queen Elizabeth also led to greater English development towards the integration of Ireland’s lands, which had otherwise long been partially left to local residents.

Tensions between various Christian groups continued throughout the 17th century, when it came to several sieges of Dublin and fighting between Englishmen and Catholic forces from Ireland. The fighting caused several Englishmen to move to Dublin, which eventually gained the Anglican majority. Under Oliver Cromwell’s rule in the 1650s, Catholics were forbidden to live in Dublin. At the end of the century, there was Anglican majority in both the capital Dublin and the Ulster region, which is the present Northern Ireland.

Despite much activity and relocation, Dublin was still very similar to a smaller, fortified medieval town in the mid-1600s. In 1649 the town had about 9,000 inhabitants. However, the population began to rise due to the large number of Protestant immigrants who came to the island from many parts of Europe, and by the year 1700 the population had passed 60,000 in numbers in the city.

In the 18th century, Dublin flourished in earnest and the city became one of the most significant in the British Empire. The population also meant that it was only London that was larger in the British Isles.

The Anglican community on the island thrived, and many Dublin residents achieved considerable wealth, which brought the city out of the Middle Ages. Many new areas were created, characterized by the new Georgian houses and neighborhoods, which continue to characterize the city in many places.

James Butler, the first Duke of Ormonde and Lord Deputy of Ireland, was one of those who started the modernization of Dublin. He introduced that houses along the Liffey River should have fine facades and face the river, which the city had otherwise used as garbage and waste for centuries.

A commission aimed to implement Georgian city plans, and many buildings around the narrow, old streets were demolished to make way for wide streets as time went by. One of the new streets was Sackville Street, now called O’Connell Street. With the new town plan, large seats were also established; in all, two large Georgian sites were built north of Liffey and three south of the river. Merrion Square and St. Stephen’s Green are examples of them.

At the beginning of the century, settling north of Liffey was most popular among the city’s wealthy. This changed after the important Earl of Kildare erected the Kildare House, now called Leinster House, to the south. It attracted many other Dublin spikes, and this area was rapidly expanded.

The 18th century also brought about a change in the composition of the city’s population. In the latter half of the century, a growing influx of rural areas around Ireland to the capital occurred, and in this way Catholics again came to the fore.

Dublin was the seat of the Irish Parliament through the 18th century, and power lay with landlords and the old English aristocracy, who eventually felt so Irish that they sought greater autonomy over the London government. Under the influence of the French Revolution and American independence, the United Irishmen were formed and developed into a revolutionary entity that wanted to transform Ireland into a republic.

In 1798, the United Irishmen planned to take control of Dublin, but their coup plans against the regime were impeded when the organization’s leaders were arrested and with the arrival of a larger crowd of English soldiers. The coup had broken down in what was to be the revolt in 1798, which transformed political life in Ireland.

The British government and the Protestant administration in Dublin were in opposition to the uprising, and the result was that the Irish parliament was abolished. It happened in the context of The Irish Act of Union, which merged the kingdoms of Ireland and Britain. Dublin’s status as a capital was brought to an end and Ireland’s status was significantly reduced. The power was transferred to London and it became the start of a long stagnation period for the city.

Dublin’s status as a capital had contributed financially to the growth of the city in the 18th century, but the many MPs and their administration and secondary services disappeared with The Irish Act of Union, which came into force from the beginning of 1801. Financially it was a setback for the Irish city, but it continued to grow in numbers.

Large mansions were put up for sale, and the formerly fine Georgian 18th-century houses and neighborhoods became dilapidated and developed into poor neighborhoods. Already in 1803 was the year of a new revolt, but it was poorly planned and easy for the English to strike.

The 19th century was a century in which there was a growing struggle for the rights of Catholic citizens among the Irish people. Since the end of the 17th century, Catholics had no influence on the city government, but that changed in 1840. It happened with the so-called Corporation Act, which changed the voting rights in Ireland. In Dublin, that meant Catholics became the majority in the City Council, and in 1841 Daniel O’Connell became new mayor.

O’Connell had in 1830 formed the political organization Repeal Association, which fought to repeal the union agreement between Ireland and the United Kingdom. O’Connell planned mass meetings, and he fought in vain to get the British government to re-establish the Irish Parliament in Dublin, among other things.

Industrialization also came to Ireland in the 19th century, but Dublin did not become an industrial city in the same way as Belfast in Northern Ireland. Consequently, Belfast grew larger than Dublin in the latter half of the 19th century, and in Dublin large numbers of residents remained unskilled and worked in places such as Guinness and Jameson Distillery.

However, new buildings were also being built in the Irish capital these years. This was the case, for example, in new Victorian suburbs, where wealthy prostitutes established themselves after relocating from Dublin itself. The transport system also evolved with the establishment of a network of tram lines. The Dublin Tramways Company put the city’s first horse-drawn trolley into operation on February 1, 1872, and it connected College Green with Rathgar.

In Parliament in London, Charles Parnell, from 1875, demanded the establishment of an Irish Parliament, and around 1900 the separatist political movement Sinn Féin was formed. These were events that played into the coming of Irish independence.

With the Irish Act of Union, Dublin’s significance had been greatly reduced through the 19th century, but by the same century its population had grown to about 400,000, which was the population around 1900.

At the turn of the 20th century, Dublin was larger, but also poorer than before. There were many areas of slum, and the neighborhood around Montgomery Street was a notorious area with high levels of prostitution. This is what Dublin, among others, James Joyce described in the literature.

Several decades of desire for local Irish rule or autonomy was adopted by the Home Rule Government of Ireland Act in 1914. That year, World War I broke out and the law was suspended and autonomy postponed. There was still great opposition to autonomy, and it was particularly pronounced in Ulster in Northern Ireland, but also significant in Dublin.

In 1916 it again revolted against the English dominion. The rebellion was turned down at the O’Connell Street post office, and the Irish once again had to postpone autonomy or independence.

Already three years later, from 1919 to 1921, an actual revolution arose, which became military and fought between British forces and Irish in the created Irish Republican Army. The war raged, and several encounters entered Irish history, such as Bloody Sunday / Bloody Sunday, where both British agents and Irish were killed on November 21, 1920. On May 25, 1921, the cityscape of Dublin was also marked; on this day, the Irish Republican Army burned the seat of the local political government in the Custom House.

The war stopped in 1921 when the British offered a ceasefire against negotiating a deal. During the war, the British government had passed the Government of Ireland Act in 1920, and it sought to set up two autonomous territories on the island of Ireland; Northern Ireland and Southern Ireland. The result of the 1921 negotiations became the Free State Irish Free State.

The Irish Free State covered the territories of Southern Ireland, with Northern Ireland opting to seize the opportunity to become political with Britain. The state had the status of Dominion and thus remained subject to the British crown. For Irish Republicans, it was not a solution that lived up to their goal of independence, and in 1922, street fighting flared up again in Dublin.

The new state took up the fight against Republicans to avoid any British military action. The Free State forces won the civil war, but for Dublin it suffered severe losses. Thus, many of the city’s finest buildings had been destroyed and Dublin had to be rebuilt.

Politically, the Irish Free State came into existence for 15 years. In 1937, the Irish government sent a constitutional proposal for a referendum, and the proposal involved the creation of the Republic of Ireland, where a president replaced the British monarch’s representative as the highest formal authority. The Constitution was adopted with just over 56% of the valid votes.

In the 1920s, the Irish Free State administration adopted several initiatives to expand and modernize Dublin. However, several of the plans were not realized until the 1930s, when more funds were available. One of the larger projects was the construction of proper housing for the capital’s poor population. On that occasion arose among others the suburbs of Crumlin and Marino. In the center, many new buildings were not possible.

Over the following decades, Dublin’s development lay quite still, and the city and country were among the poorest in Western Europe. It took until the 1950s and 1960s before the new buildings really got going again. Especially in the 1960s, much was developed in the city, and much of Dublin’s 18th-century building was lost in redevelopments that made way for new offices and apartments.

The brutal demolition of ancient architecture today was part of an Irish flow that sought to put away physical symbols of the colonial period of the past. Perhaps the most manifest example was the pillar Nelson’s Pillar, which stood in Dublin from 1809 to 1966, where the Irish destroyed the British memorial. In the 1970s and 1980s, things were expanded slightly differently than in the 1960s. During these decades the Georgian facades were retained and newly built behind the facades.

Ireland joined the European Community (EC) in 1973 as one of Western Europe’s poorest regions. Through the membership of the EC, which has since joined the European Union, the Irish economy, through European means, underwent significant developments from the 1980s.

In the 1990s, Ireland’s economy boomed and it could be seen in Dublin’s streets. Before letting parts of the city as construction sites or dilapidated areas, but with the new economic situation, countless buildings were started. New homes and offices were popping up in many places in Dublin such as the International Financial Services Center along North Quays.

Dublin’s transportation system was also expanded. The city’s old trams had run until the 1950s, when buses had taken over the traffic. In 2004, Luas’ trams opened and the railway network has since expanded both north and south of the Liffey River. Dublin Airport has also been expanded and welcomes a large number of tourists each year to Ireland and the capital Dublin.

Dublin, Ireland[/caption]

Dublin, Ireland[/caption]

Overview of Dublin

Dublin is the capital of the Republic of Ireland, where one of the major things on the bucket list is the Irish atmosphere, which is reflected in the famous Irish pubs with Irish music. It is part of Ireland that you must remember to bring home from the green island, and you will also find many nice sights, monuments and museums in and around the capital,

Dublin, however, is also much more than pubs and coziness in the centrally located Temple Bar district. This includes the Vikings’ historical settlement, the elegant and intellectual environment of Trinity College, the large shopping districts, the green, Georgian 18th-century parks in the middle of the city, and of course the famous statue of Molly Malone.

About the Whitehorse travel guide

Contents: Tours in the city + tours in the surrounding area

Published: Released soon

Author: Stig Albeck

Publisher: Vamados.com

Language: English

About the travel guide

The Whitehorse travel guide gives you an overview of the sights and activities of the Canadian city. Read about top sights and other sights, and get a tour guide with tour suggestions and detailed descriptions of all the city’s most important churches, monuments, mansions, museums, etc.

Whitehorse is waiting for you, and at vamados.com you can also find cheap flights and great deals on hotels for your trip. You just select your travel dates and then you get flight and accommodation suggestions in and around the city.

Read more about Whitehorse and Canada

Canada Travel Guide: https://vamados.com/canada

City tourism: https://visitwhite-horse.ca

Main Page: https://www.vamados.com/

Buy the travel guide

Click the “Add to Cart” button to purchase the travel guide. After that you will come to the payment, where you enter the purchase and payment information. Upon payment of the travel guide, you will immediately receive a receipt with a link to download your purchase. You can download the travel guide immediately or use the download link in the email later.

Use the travel guide

When you buy the travel guide to Whitehorse you get the book online so you can have it on your phone, tablet or computer – and of course you can choose to print it. Use the maps and tour suggestions and you will have a good and content-rich journey.

Built from 1729 to house the Irish Parliament, this building is therefore of particular historical interest. The name of the building is also known as Parliament/Parliament House, and it served as the seat of both the House of Commons and the House of Lords in the Kingdom of Ireland until the year 1800. With the so-called Act of Union from 1800, the Kingdom of Ireland was dissolved and Ireland instead became part of the union United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland.

The Irish Parliament was located in Chichester House from the 17th century. By the beginning of the 18th century, this building had become dilapidated and too small to house the parliament. In 1727 it was therefore decided to spend £6,000 on a new building which became the present Parliament House. The building was designed by the architect Edward Pearce and built in the years 1729-1739.

Pearce’s original building is only part of the present complex on the site, and his work can be seen to the south with columns and colonnades. In 1787-1787 Parliament was extended with the portico to the east, and it was James Gandon who was behind the extension, which formed the entrance to the Irish upper house, the House of Lords. In 1787 the extension of Parliament to the west and the street Foster Place were also built. It happened by Robert Parke’s design.

When Parliament moved to London with the Act of Union in 1800, the Irish national bank, Bank of Ireland, took over the place. It happened with a clause that the former parliament building could no longer be used for political purposes. The Bank of Ireland was based here until the 1970s, when the institution moved to a modern building in Lower Baggot Street; in 2010 the bank moved to an address on Mespil Road.

Today, it is the House of Lords’ former meeting room that has been preserved as the most remarkable room in the building complex. Here you can experience an impressive hall with large 18th-century wall paintings and a fine chandelier from 1765. The House of Commons was the House of Commons, and their meeting hall was furnished with the Bank of Ireland as the central banking hall.

Irish folk music and Irish songs are known over large parts of the world, and popular songs include the song about Molly Malone. In the show, the girl Molly Malone walks the streets of Dublin selling seafood from her cart. Molly Malone is so far a fictional character, but many people have had a similar name over the years, and the much-sung Molly Malone’s life could well have taken place in historic Dublin. Some point to the fact that the story in the show could have been taken from the life of the real Irish capital in the 17th century.

Today, a statue of Molly Malone can be seen next to St. Andrew’s Church. Designed by Jeanne Rynhart, the statue was unveiled on 13 June 1988 during Dublin’s centenary celebrations. The statue originally stood on Grafton Street and it is planned to move it back there. By the way, June 13th bears the title of Molly Malone Day, and it is celebrated every year.

Custom House is the name of Dublin’s distinguished old customs building, which was built in neoclassical style in the years 1781-1791. It was the architect James Gandon who designed the large building, the facades of which were adorned with coats of arms and sculptures symbolizing Ireland’s rivers.

The customs functions in the Custom House were after some time transferred to London, and instead various public offices such as the tax police were set up in the large building, and thus it never came to be empty. Dublin’s port had also moved away from the city centre, and the Custom House’s location was therefore no longer as central as in the 1790s.

In 1921, the Custom House was badly damaged in a fire, and a rebuild was carried out over the following five years. However, the work only partially completed the town’s customs house, and it took until 1991 before the building was fully restored.

Today, exhibitions about the history of the Custom House are set up here, and you can also take a closer look at James Gandon’s buildings in Ireland. Gandon was born in English London in 1743, and the Custom House was his largest large-scale project.

Dublin is known for its Georgian neighborhoods. The rows of houses around Merrion Square are a magnificent example of precisely this type of architectural structure. The period is the 18th century, when there was economic prosperity and thus great building activity in Ireland.

It is recommended to take a walk around the square to really experience the houses and thus the typical impression of the period. The north side in particular is characteristically Georgian with the decoration of the houses’ entrances, wrought iron balconies, the colors of the doors and other characteristics that make the houses of this period so attractive in the streetscape.

The square was laid out in 1762 and was largely expanded in the early 1800s. It was not least the Earl of Kildare’s construction of a new residence, Leinster House, that made this area south of the River Liffey popular. With the construction of Leinster House, Merrion Square, Fitzwilliam Square and St. Stephen’s Green all laid out, and many of the city’s leading figures moved from the north side of the city to new townhouses around the squares.

At Merrion Square, in the square’s small park, you can see a statue of Oscar Wilde, who lived at the address Merrion Square 1 in the years 1855-1876. Originally, the Wellington Testimonial memorial was to have been erected in the square to commemorate Arthur Wellesley’s military victories, but due to resident protests it was instead erected in Phoenix Park. There is public access to the park at Merrion Square, but until the 1960s access was only available to residents with their own key.

O’Connell Street is Dublin’s main thoroughfare. The street is about 500 meters long and it is up to 49 meters wide. The street was called Drogheda Street back in the 17th century, and it was not until the 18th century that the current O’Connell Street was created as a street.

It was Henry Moore who, as Earl of Drogheda, had laid out the 17th-century street, and in the following century the banker and property man Luke Gardiner expanded the street according to the European model. Curtains would create a tree-lined boulevard of beautiful mansions and townhouses.

Luke Gardiner’s original site did not extend to the River Liffey, but an extension was the idea with the new street. Gardiner died in 1755 before this extension to the Liffey had been completed. The city government in Dublin chose to implement the plans later in the 18th century, and thus one of the most elegant streets in Europe of the time arose. Gardiner called the new street Sackville Street, and it was named after the then Lord Lieutenant, Lionel Cranfield Sackville.

The street retained the name Sackville Street until 1924, when it was named after Daniel O’Connell in memory of his political struggle in the 19th century for Catholic and Irish freedom in Great Britain.

Today there are not many original houses left, but after a series of demolitions in the 1970s in particular, new ones have been built, and there is also a lot of art and statues to see.

The most impressive building is the General Post Office, and of the monuments, the O’Connell Monument and the Spire of Dublin are probably the most well-known and worth seeing. The Spire of Dublin is a 120 meter high spire made of stainless steel, which was designed by Ian Ritchie Architects and completed in 2003.

On the site of the Spire of Dublin, Nelson’s Pillar stood in the years 1808-1966, when the monument was destroyed by a bomb blast.

Grafton Street is the name of Dublin’s most popular shopping street. The street stretches from St Stephen’s Green to the south to College Green to the north, and it is therefore centrally located in the Irish capital.

Grafton Street is named after Henry FitzRoy, who held the title of 1st Duke of Grafton. FitzRoy was the unofficial son of Charles II of England, who owned land on the site of present-day Grafton Street. The street was developed and thus effectively laid out by the Dawson family from the year 1708, and Grafton Street became a popular residential area. With the later construction of Carlisle Bridge, the current O’Connell Bridge, Grafton Street changed to be one of the city’s busy streets.

The Four Courts is the name of this building, which houses four of the Republic of Ireland’s most important courts; The Supreme Court, the Court of Appeal, the highest civil and criminal court called the High Court and the local court Dublin Circuit Court.

However, the name Four Courts comes from the British era, when the building was built for the Court of Chancery, Court of King’s Bench, Court of Exchequer and Court of Common Pleas respectively.

The large courthouse was built in the period 1776-1802. The first part of the design was drawn by Thomas Cooley and completed by James Gandon after Cooley’s death in 1784. Gandon was also behind, among other things, the Custom House in Dublin and has thereby left a distinguished architectural mark on the city.

Historically, the Four Courts’ quiet existence as administrative court offices was significantly changed in the first half of the 20th century. 1922 was the year a group of Irish people occupied the building in protest against the Anglo-Irish Treaty that had established Ireland as part of the British Empire. The Four Courts were bombed and destroyed during this occupation.

In the following years, the Four Courts was rebuilt according to original designs, and the site was reopened in 1932. In the building under the large dome, you can see and read about its history.

The world-famous author James Joyce was born in Dublin, where all his great stories take place. Ulysses is his most famous book and it is based on real life in Dublin on June 16, 1904.

The James Joyce Center is housed in the Earl of Kenmare’s town house from 1784, and here you can see a fine Georgian interior. The exhibition itself in the center examines James Joyce’s life and of course his works. If you are interested, you can get information on the spot about walks in the area where James Joyce or the characters in Ulysses have had their time.

On the western outskirts of Dublin lies the 712-hectare green area called Phoenix Park. It is a very popular park, which is used extensively by locals, and there are also many activities and a lot to see for visitors to the city.

The Phoenix Park area was conquered by the Normans in the 12th century, and the land here was given to the Order of St. John, which from the 16th century was known as the Order of Malta. The Knights of the Order established an abbey here, but they lost the land when King Henry VIII dissolved the monasteries in 1537. In the 17th century, the land passed to the king’s representatives in Ireland, and in 1662 the later park was laid out as a hunting ground. The park got its current size in 1680 and it was opened to the public in 1745.

You can take lovely walks in Phoenix Park along paths and over large lawns. There are wild game in the park, and you can also visit Dublin Zoo here. The garden opened in 1831 with animals from the English London Society.

You can also see several of Dublin’s most important monuments around Phoenix Park. The Wellington Testimonial is seen at the entrance to the park. It is a 62 meter high obelisk that was erected to commemorate the Duke of Wellington’s victories during the Napoleonic Wars. The obelisk is the tallest in Europe, and it should have been even higher, but during construction the project ran out of money. The Wellington Testimonial was originally intended for a square in Merrion Square, but the square’s residents protested, so the installation was moved.

Another monument is the Phoenix Column, which consists of a central column with a bird Phoenix rising from the ashes. It was Lord Chesterfield who had the Phoenix Monument erected in 1747. You can also see the Papal Cross in Phoenix Park. It has been erected on the very spot where Pope John Paul II held mass in 1979 for more than a million Irish people.

Between the monuments and the lawns is the official residence of the Irish president, Residence of the President/Áras an Uachtaráin. The house was completed in 1751 according to Nathaniel Clements’ design. In the 1780s, Clements’ house was acquired by the British monarch’s representative in Ireland and used as a somme’s residence, thereby supplementing the viceroy’s quarters at Dublin Castle. Since then, the building was named Viceregal Lodge, and the viceroys lived here for most of the year. They mainly used Dublin Castle from January to March, when there were many social duties.

In his time, it was not only the viceroy who had an official residence here in Phoenix Park. The same applied to the appointed Chief Secretary and Under Secretary who worked during the British era. The residence of the Chief Secretary is today the American ambassador’s residence, but the Under Secretary’s residence has been demolished.

In the 1900s, the American Chester Beatty donated his unique collection of literature and manuscripts to the city of Dublin. Among other things, you can see up to 6,000-year-old stone tablets, papyrus, beautiful editions of the Bible and many Asian books that have been prepared in unusual materials such as bark or jade. The library was founded in 1950 and since the year 2000 it has been located in its current location at Dublin Castle.

Similar to Dublin Travel Guide